It was like renewing my youth to meet him – to hear him ask me if I remembered the “Fourteen-Fifteen” puzzle, or the trick donkeys, or “Get Off the Earth.” And to hear how those old friends of boyhood’s days came to exist and something of their history since I first knew them – that was like meeting an old, old friend and hearing him tell the story of his life. Yet one can never speak of the “Fourteen – Fifteen” puzzle or “Get Off the Earth” as old. They are perennially new. Long after the brain that gave them life is quieted – and may that be many, many years hence – a new generation will be watching the Chinaman fade away at the movement of the pivoted card; or shifting the counters so as to compel Fourteen and Fifteen to take their places in serial relation. Sam Loyd is not of one generation any more than he is of one country – he is universal and everlasting.

A quiet man, with a ready tongue and a quick wit showing through a twinkling eye – that is what first impresses you about the famous puzzle – man. He is reputed to have made a million dollars out of that active brain; yet he is as modest of demeanour and as quiet of dress as though he were a clerk in a business establishment at twenty-five dollars a week. His moustache is white now and his head a little bald – for has he not been entertaining the world for fifty-five years with his odd conceptions? But I can fancy him when he made his first puzzle fifty-five years ago, younger-looking but no more acute mentally than he is now, when he handles sometimes one hundred thousand letters a day from his correspondents, eager to share in the prizes he offers for the solution of his puzzles.

Out of his side-pocket, as he sat down in the wicker rocking-chair in my private office, he took something round, and looked at it with an amused smile.

“I didn’t bring it along to show you,” he said, “but perhaps it would amuse you.”

I took it from him and examined it. You have doubtless seen what the Chinese have done upon the same lines – carving a ball within a ball, or a fully-rigged ship in a bottle. This was a wooden ball, perhaps two inches in diameter, with a careful reticulation, within which appeared another reticulated ball, moving freely, and within that another and another and another – five in all.

“I did it last week,” he said, “out of a croquet-ball.

Again the hand went into the capacious pocket, and a curious bit of carving came out. It was a forked twig, taken just as Nature made it; and, with a face carved under a natural hat at one end and two feet outlined at the other, it was Rip Van Winkle to the life. Mr. Loyd said he had found it in the Catskills Rip’s own country. “Doesn’t he look as though he had been asleep a long time?” he asked. Certainly Rip’s wooden legs were warped as though he had been out in the night air a long time. Mr. Loyd made another exploration, and brought out a snake – red-mouthed, coiled for a spring. “I found that piece of wood up at Ticonderoga, where it is said Ethan Allen killed the rattlesnake,” he said. “I haven’t changed it at all. I am always coming on odd things like that. I have a cabinet at home full of them.”

Evidently Mr. Loyd’s faculty of observation is acute. You or I would not have seen the rattlesnake in the root, or the little old man in the forked twig.

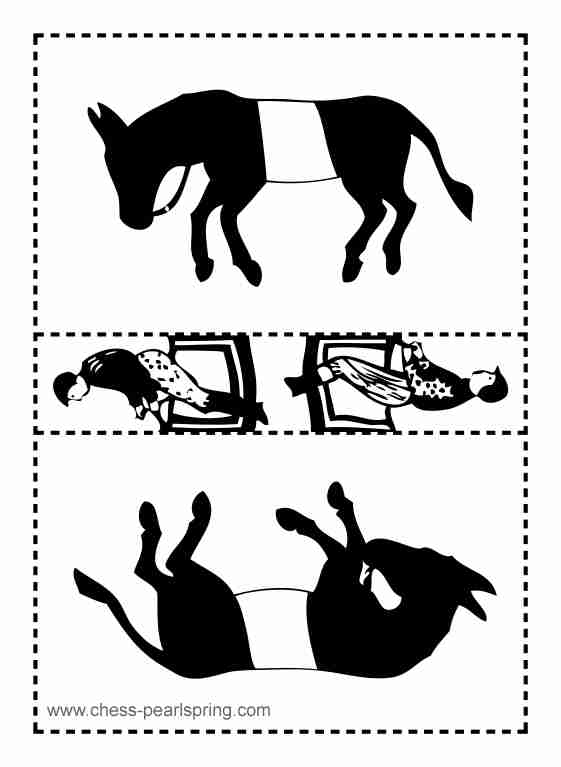

He does not tell it of himself, but Mr. Loyd as a boy had a power of imitation and an aptness at ventriloquism which made trouble for all who came within his mischievous activities’ range. He was just a keen-minded vigorous boy, as alert physically as he was mentally. And of this material they tried to make a civil engineer. He look the course and started on the practice of the profession. But already Nature had begun to point out to him the sphere in which he was spend his life. With the talent for creating puzzles half developed in his brain, what had he to do with civil engineering and its slow road to success and wealth? When he was still only seventeen, and just beginning to be an engineer, he devised a puzzle which made for him in a few weeks ten thousand dollars. It decided him abruptly not to spoil a good puzzle-maker for a poor civil engineer. This puzzle is one which will live always, I believe, for it is as great a favourite today as it was half a century ago. It is the puzzle of the trick donkeys.

“Fancy!” as Hedda Gabler’s husband so often reiterates, that not millions but thousands of millions of these have been sold, and you will understand in what a curious way Mr. Loyd found the key to success – not in great things, but in little things often multiplied. In fact, it is his theory, verified so well in his own experience, that it is the little and not the great thing that is most often profitable.

“Fancy!” as Hedda Gabler’s husband so often reiterates, that not millions but thousands of millions of these have been sold, and you will understand in what a curious way Mr. Loyd found the key to success – not in great things, but in little things often multiplied. In fact, it is his theory, verified so well in his own experience, that it is the little and not the great thing that is most often profitable.

“I am still taking orders for those donkeys in million lots,” he said. “When I first sold them I had my own printing outfit; but now I have the printing done by someone else. Of course, my legal rights in all my early devices have lapsed by this time, but copyrights and patents mean very little to me. People don’t care for my puzzles unless they can have them with my name on them. Those trick donkeys have been associated with a great many incidents in the lives of business houses and business men. There is a big dry goods arid department store in New York which uses a star as a sort of trade-mark. The donkeys were responsible for that. When the firm started in business they gave me an order for a million copies to give away. When I was setting up the card, I noticed that there was a space between the donkeys which looked blank, so I stuck in a star. When I saw the head of the house later, he said to me, ‘What is the meaning of that star, Mr. Loyd ?’ ‘To make little boys ask questions,’ I answered. He laughed and said, ‘You see, it made me ask one.’ His partner came up at this moment and said, ‘We’ve used that star now in connection with these million cards; why not use it hereafter as a trade mark?’ And that was the origin of an emblem which has since become famous in the world of trade.

“I recall another incident of the donkeys’ career. P. T. Barnum, who was running his circus when the donkeys were most popular, asked me if I would take ten thousand dollars and call them ‘P. T. Barnum’s trick donkeys.’ I said I would, and about that time I was filling an order from a big Philadelphia concern for a large number. So I shipped them the cards with Barnum’s name on them. Back came a letter from the head of the house, saying, ‘We have several tons of advertising literature of P. T. Barnum on hand, awaiting your orders. I’m enough of a humbug myself without advertising through my store that much greater humbug Barnum.’ For a time I was afraid I should lose my cards, but I went to Philadelphia, explained the matter, and persuaded the house to take the cards and use them.”